Like a bird of paradise, 5 Pointz presides over a bleak stretch of Queens, next to a railyard and between roads that lead deeper into ever bleaker Long Island. But the unexceptional surroundings only make this “Mecca of Graffiti” all the more astounding: five stories of mustard-colored walls entirely covered with what is tactfully known as “aerosol art.

”It’s a modern-day Guernica in Long Island City, as the neighborhood is called, except this art was made not in response to war but to the terror and promise of modern urban life. A black man in a hoodie looms at eye level, rendered in Seurat’s pointillism. You may see a likeness of Biggie Smalls or Van Gogh, samurai and buxom women, all painted by different taggers, all somehow coexisting in this fruitful chaos.

This plein air exhibit of street art is soon coming to an end, though; the building is to be demolished to make way for condominiums. When news of the City Council’s approval of the move came last week, NY’s Gothamistlamented, “Somewhere an empty can of spray paint has rolled into a gutter, dented and rattling no more.

”And somewhere else, maybe right down the block, Banksy is at it. By pure coincidence, the British street artist has chosen October for a month-long residency in New York, putting up one of his graffito (or, occasionally, a performative piece like a truck full of stuffed farm animals driven around the city) somewhere in the city each day. The confluence of the two events — the imminent destruction of 5Pointz and Banksy’s residency — have made graffiti the talk of New York again.

Graffiti is one of those intractable issues, like Middle Eastern politics: Everyone has an opinion, and everyone is right. The debate, which probably began when some Roman scrawled a filthy quip on a Coliseum wall, still matters in the glass-and-steel New York of 2013, in which there are an estimated 6,000 “public-sector surveillance cameras” that may help in the identification and capture of illegal taggers (and perhaps a few terrorists).

Modern graffiti may have started as a response to urban blight, the emptying of cities in the postwar era and the absence of authority (all that empty wall space, all that free time). In its latest iteration, the form has been mastered by Banksy, a British artist whose real name is not known outside a small circle of associates. He has made a popular film, Exit Through the Gift Shop and his work has sold for hundreds of thousands of dollars, much to his chagrin, for Banksy prefers notoriety to fame. “Commercial success is a mark of failure for a graffiti artist,” he told the Village Voice.

And now he has come to New York for a project he calls “Better Out Than In.” Not everyone is pleased, least of all those who remember neighborhoods like the Lower East Side before the Olsen twins started hanging out at Sons of Essex, when unruly beards belonged not to hipsters but to Bowery bums. The Daily News (where I was once an opinions editor ) welcomed Banksy to New York by calling him “criminal” and noting that the city spends some $2 million on graffiti clean-up each year.

But it is hard to argue that Banksy’s stenciled works are purely a nuisance. His first work here, in Manhattan’s Chinatown, depicted a newsboy standing on the shoulders of another as he grasped for a spray paint can inside a sign that reads “Graffiti Is a Crime.” Later, a delivery truck became a “mobile garden,” in the words of Banksy’s website. That website prominently displays a quote from Cezanne: “All pictures painted inside, in the studio, will never be as good as those done outside.” Paul may have been talking about lily ponds and haystacks but, well, point taken

.And while some grouse at graffiti’s recrudescence, many have embraced Banksy’s maverick intention to turn whatever wall he wishes into an exhibit. A Banksy beaver appeared in East New York, a tough stretch of Brooklyn. Hipsters flocked to see the work, and some enterprising locals began charging people to look at it, hiding the beaver behind a cardboard box. That was a brilliant comment on the nature of art, its commodification, its ability to reach the masses. If Banksy didn’t put these guys up to the task, then he’d at least have a good laugh at the expense of the Gagosians of this world. Equally clever was the stall he set up in Central Park “selling 100% authentic original signed Banksy canvases. For $60 each.” The stall was watched over by an old man in a baseball cap, and the first customer bargained him down 50%. Take that, Mary Boone.

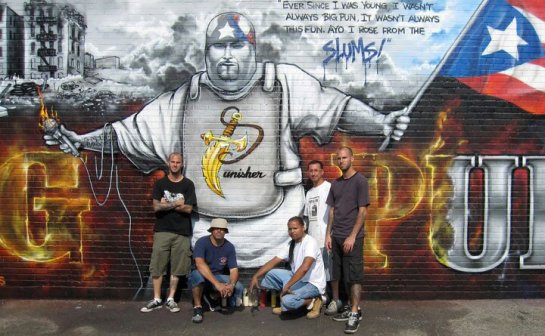

But while Banksy is being celebrated, 5Pointz is headed for demolition. The building’s owner, Jerry Wolkoff, has long allowed the graffiti elder statesman Jonathan Cohen — a native of the South Bronx who goes by Meres — to curate a sort of open-air exhibit of graffiti on 5Pointz’s outer walls (the name refers to the city’s five boroughs, as well as to the historic lower Manhattan neighborhood popularized by Gangs of New York). But you can’t just show up with a spray can and a dream; Cohen screens all applicants, making 5Pointz a gorgeously unruly group show. It stands only a couple hundred yards from PS 1, the Museum of Modern Art branch whose generally avant-garde works looks tame in comparison.

5 Pointz is being razed to make way for two buildings containing 1000 units. Wolkoff assures the city that there will be outdoor space for “aerosol art,” and there is no reason not to take him at his word. But graffiti is supposed to be transgressive, its illegality intrinsic to its artistry. Even 5 Pointz was a sort of compromise with authority. To paint graffiti in the shadows of condominium towers will only be more so.

As some struggling cities are being given over to the creative classes (Detroit welcomes hipster farmers and Baltimore dreams of being the next Portland) the artform that defined and was inspired by urban blight is becoming predictably tamed. Across the East River, at the Red Bull Gallery — yes, that Red Bull — in Chelsea, a show called “Write of Passage” opens this month. It is, according to organizer Mass Appeal, “a six-week educational program exploring the impact of American graffiti art on global culture.” It will likely involve sitting in chairs and viewing slides, not vaulting over fences at Bronx rail yards to cover slumbering trains in tags.

The program is headed by Sacha Jenkins, a graffiti artist from Queens who recently told the New York Postthat Banksy’s tear across the city had not left him impressed: “I think with your blue-collar [graffiti artist], there’s not much respect for Banksy, because it’s not akin to what real graffiti is. And I’m sure there’s a bit of jealousy about the financial success he’s had.

”Are there still blue-collar taggers out there? Doubtlessly there are, scrawling whatever “real graffiti” may be. But their space is being threatened, while their work, if it is any good, is being commodified. While we may not all love graffiti, we know a marketing opportunity when we see one.